Melanoma

What is a Melanoma?

Melanoma is one of the deadliest forms of cancer, and often appears as an atypical mole. Melanoma is a malignant cancer arising from pigment cells in the skin - known as melanocytes.

The major risk factor for melanoma is the number of moles you have. The most important factor in survival is early diagnosis.

Melanoma is the fourth most common major malignancy in Australia, and we have the world's highest incidence along with New Zealand. Queensland has the highest incidence of any state in the world.

Melanoma is more commonly diagnosed in men than women. 1 in 17 Australians will get melanoma. This means in your life you will know several people who will be diagnosed with this disease.

Unfortunately, 1 out of every 120 Australians will die from it. You will know one or two of these people too. In 2016, it is estimated that 13,283 new cases of melanoma will be diagnosed in Australia, accounting for nearly 10% of major malignancy diagnoses. It’s estimated 1,774 will die.

5 Australian Die of Melanoma - Everyday

Australian Melanoma incidence and death rates have been increasing:

At the same time overall survival has been improving. 5 year survival rates from melanoma have improved from 85% in 1982 to 90% in 2016 (est).

When treated early the majority of melanomas are curable.

Melanoma Risk Factors

Everyone is at some risk for melanoma, but increased risk depends on several factors. Anyone with a history of sun exposure can develop melanoma. However groups of people at greater risk include:

Large Number of Moles

People with large numbers of moles, especially unusual or unique looking moles (Dysplastic Naevi). There are two kinds of moles: Congenital - the small brown blemishes, growths, or "beauty marks" that appear in the first few years of life in almost everyone and - Acquired moles which arise up to the age of 40 and tend to go away (regress) after the age of 70.

The nature of the moles on your body is also significant. Atypical moles, also known as Dysplastic Naevi, confer a higher risk. Atypical moles can be precursors to melanoma, and having them puts you at a much higher risk of melanoma. These are usually multiple, and are uniquely different from each other in size, shape, colour, outline and so on. Often many have one or more of the ABCD characteristics.

Some people with a large number of (>50) Dysplastic Naevi who have had one removed and confirmed to be either precancerous (Dysplastic) or melanoma, are considered to have Dysplastic Naevus Syndrome which confers an increased risk of melanoma in the order of 20-30 times. But irrespective of the type, the more moles you have, the greater your risk of melanoma.

Sun Exposure

Both UVA and UVB rays are dangerous to the skin, and can induce skin cancer, including melanoma. Blistering sunburns in early childhood especially increases the risk, but sunburns later in life and cumulative exposure also may be factors. People who live in higher UV locations develop more skin cancers, and the highest UV levels are on the Equator. Avoid using a tanning booth or tanning bed, since it exaggerates exposure to UV rays, raising your risk of developing melanoma and other skin cancers.

Skin Type

As with all skin cancers, people with fairer skin are at highest risk. Common risk attributes like fair skin, freckles, blond or red hair, and blue, green, or grey eyes. They have a tendency to burn rather than tan.

Personal History

People who have had one melanoma are at risk of developing others, in the same area or elsewhere on the body. If you’ve had a melanoma you have a 10 times higher risk of developing another skin cancer of any type and so routine reviews are advised on a 6 monthly basis.

This risk of recurrence, and your risk of developing another melanoma is higher - especially in the first two years after diagnosis. People who have or have had Basal Cell Carcinoma or Squamous Cell Carcinoma are also at increased risk for developing melanoma.

In simple terms every cancerous and pre-cancerous skin lesion you’ve had numerically contributes to your risk of melanoma.

Compromised Immune System

Compromised immune systems as a result of chemotherapy, an organ transplant, excessive sun exposure, and diseases such as HIV/AIDS or lymphoma can increase your risk of melanoma.

Family History

Heredity plays a major role in melanoma. About one in every 10 patients diagnosed with the disease has a family member with a history of melanoma. If your mother, father, siblings or children have had a melanoma, you are in a melanoma-prone family. Each person with a first-degree relative diagnosed with melanoma has a 50 percent higher chance of developing the disease than people who do not have a family history of the disease.

This is especially relevant where the close family member was diagnosed with melanoma under the age of 40.

In Europe family history has a greater role in the pathogenesis of melanoma and 70 percent of melanomas have a genetic basis.

When melanoma is diagnosed, it is standard practice for your Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic Doctor to recommend that close relatives be examined without delay for melanoma and for the presence of unusual or atypical moles.

Familial Dysplastic Naevus Syndrome

When >50 atypical moles are found in an individual belonging to a melanoma family, the condition is known as Familial Dysplastic Naevus Syndrome (also known as FDNS). People with this syndrome are at the greatest risk of developing melanoma. In contrast, a research study found that those family members who did not have atypical moles were much less likely to develop melanoma.

Genetic Risk Factors

Great strides are being made in the understanding of the genetics of melanoma, and many key discoveries have been made giving rise to new dimensions in treating this disease. A mutation (a “glitch” in the DNA sequence) in a recently discovered gene, BRAF, can play a part in causing many melanomas. This mutated gene is found in about half of all melanomas. BRAF is called a "switch" gene, because mutations can turn it on abnormally, leading to uncontrolled cell growth and cancer.

The discovery of BRAF was an exciting research breakthrough, and with the development of vemurafenib to inhibit BRAF in 2011, patients with metastatic melanoma the world over have seen benefits.

Increasing understanding of the BRAF gene could lead to the development of new diagnostic tools and has already led to approval of several new and improved drug therapies.

The mutations most commonly seen in familial melanoma occur in another gene, p53. When this gene is in its normal state, it functions as a tumour suppressor, giving damaged cells the chance to repair themselves without progressing to cancer. However, when the gene is altered, it becomes unable to perform this function, and cancer can result. Complicating matters, new research shows that the same ultraviolet (UV) rays that produce skin damage can damage p53, causing the alterations that eliminate its ability to suppress tumours.

A number of gene mutations in addition to p53 and BRAF have been associated with familial melanoma, notably the CDKN2A (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A) gene. In the future, families might be screened to identify those members who are carrying a defective gene as carriers of this mutation may also be at risk of pancreatic cancer, and brain tumours have been reported in some families.

If, as a result, carriers become particularly vigilant in watching their moles and having regular total-body skin examinations, they are more likely to detect melanomas at the earliest stages, when the chances of a cure are far higher. In fact, testing is now commercially available for the presence or absence of the CDKN2A gene, but the consensus of melanoma experts is that genetic testing is not yet warranted for most people and should be done only in the context of clinical trials.

Where Are Melanomas Found?

It can occur in or on any part of the body - even parts that have never been exposed to the sun. In rare cases - melanoma can even start inside the body.

They can appear anywhere but most commonly develop on parts of the body that receive high or intermittent sun exposure (head, face, neck, shoulders, back, and back of calves).

What Causes Melanoma?

Melanoma risk increases with exposure to UV radiation, particularly with episodes of sunburn (especially during childhood). 95% of melanomas in Australia result from skin damage caused by:

- Cumulative long-term sun exposure

- Intermittent overexposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun (typically leading to sunburn)

Most melanomas occur on parts of the body exposed to the sun — especially the face, ears, neck, scalp, shoulders, back, and back of the calves, but many can be found in areas that are only burned or exposed occasionally - such as the abdomen or upper thighs

It is not possible to pinpoint a precise, single cause for a specific tumour, especially tumours found on a sun-protected (rarely exposed) area of the body or in an extremely young individual. Some melanoma can also result from less common causes such as contact with arsenic.

Symptoms of Melanoma?

Melanoma may have no visible symptoms, however it can be associated with observable changes in a mole. Other symptoms may include new and evolving dark areas under nails or on membranes lining the mouth, vagina, or anus.

As a general rule, to spot either melanomas or non-melanoma skin cancers (such as Basal Cell Carcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma), take note of any new moles or growths, and any existing lesions that begin to grow or change noticeably.

If you observe two or more of the signs below, you should consult the Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic immediately.

- Changing Mole - the most obvious sign is change in a mole. This could be size (gets larger or rarely smaller), shape (becomes irregular), colour (darkens, lightens, or becomes irregularly coloured), or the border becomes more irregular or less well defined

- New Mole - another major clue is the appearance of a new mole. Over 40 years of age this is a rare event and should prompt professional evaluation to rule out melanoma. This is also recommended for younger people, especially if the new mole continued to change

- Mole Appearance - including asymmetrical shape, irregularly bordered, multi-coloured or tan/brown spot or growth

- A shiny bump or nodule that is often black/brown, pink, red, blue, or white. Especially one which in new, or has changed rapidly over just a few weeks or months

- An open sore - that bleeds, oozes, or crusts and remains open for a few weeks, only to heal up and then bleed again. A persistent, non–healing sore is a worrying sign for melanoma especially if it occurs on a mole

- A reddish patch - or irritated area, which may develop a crust. It may itch or hurt. Mostly they are not tender and have no associated discomfort Pigment growing in a scar - any pigmented patch growing in a previous surgical or other scar, whether or not the scar was for the removal of a mole or melanoma

- A scar-like area that is white, yellow or waxy, and often has poorly defined borders; the skin itself appears shiny and taut. This warning sign may indicate the presence of an invasive melanoma that is larger than it appears to be on the surface

Melanoma can sometimes resemble non-cancerous skin conditions such as psoriasis or eczema, the clue being that melanomas don’t seem to go away or respond like benign conditions often do

Moles, brown spots and growths on the skin are usually harmless — but not always. Anyone who has more than 50 moles is at higher risk for melanoma. The first signs can appear in one or more unusual looking moles. That's why it's so important to get to know your skin very well and to recognise any changes in the moles on your body.

A melanoma generally changes at a different rate and/or with a different pattern than a patient's other moles. This reflects the concept of "E" for evolution that was recently added to the ABCD acronym.

Self Examinations for Melanoma

As it is so vital to catch melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer, early that Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic recommends you use three strategies to recognise the disease in its earliest stages. Three common skin check methods are:

- ABCDEs

- Ugly Duckling

- Unique Change That Persists Beyond 2-3 Weeks (anywhere, anything)

ABCDE Melanoma Self Check

Look for the ABCDE signs of melanoma, and if you see them make an appointment with the Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic immediately as early diagnosis is essential.

- Asymmetry - A benign mole is usually symmetrical. If you draw a line through the middle, the two sides will match, revealing its symmetry. If you draw a line through asymmetric mole, the two halves will not match, revealing its asymmetry, which is a warning sign for melanoma.

- Border - A benign mole has smooth, even borders, unlike many melanomas. The borders of an early melanoma tend to be uneven. The edges may be scalloped or notched.

- Colour - Most benign moles are all one colour — often a single shade of brown. Having a variety of colours is another warning signal. A number of different shades of brown, tan or black could appear. A melanoma may also become red, white or blue, or any combination.

- Diameter - Benign moles usually have a smaller diameter than malignant ones. Melanomas usually are larger in diameter than the eraser on your pencil tip (6mm), but they may sometimes be smaller when first detected.

- Evolving - Common, benign moles look the same over time. Be on the alert when a mole starts to evolve or change in any way. When a mole is evolving, consult your Doctor at the Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic. Any change — in size, shape, colour, elevation, or any new symptom such as bleeding, itching or crusting — may point to danger. Digital skin mapping and dermoscopic monitoring are the most sensitive ways to assess evolution in moles.

Ugly Ducking Self Check for Melanoma

The ugly duckling approach is a handy observational technique for finding melanoma.

It derives from the observation that naevi in the same individual tend to resemble one another, and that melanoma often deviates from this almost repetitive pattern. Look for a unique outlier against the background of similar-looking moles.

Six different clinical scenarios where outlier lesions ("ugly ducklings") should prompt suspicion:

- A new mole develops over 40 years of age

- Larger and/or darker than the surrounding moles

- Small and red or a unique appearance on a background of multiple large dark moles

- Few or no other moles or one dominant mole pattern with slight variation in size

- Has two predominant patterns, one larger and one with small, darker irregular areas

- Lacks a regularly shaped outer border

- Any changing lesion, one with symptoms, or if visually atypical should be considered a suspicious outlier.

Patients are advised to contact the Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic if they notice a mole that is changing uniquely.

Children With Melanoma

Children get melanoma, but not as often as adults. They may arise in young children, especially those who have a family history of early onset melanoma (ie under 40 years of age). Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic Doctors, therefore, advise parents to make a point of studying a child's skin from infancy onwards. If there is anything on the child that is changing uniquely for more than 2-3 weeks then make an appointment for the child at the Clinic without delay.

A clue in children is non-proportional growth. This relates to the fact that most melanomas on children grow faster than they do - meaning that normal moles often grow at the same rate as the child, but malignant lesions often grow even faster.

If the question is in the mind of the parent as to whether a particular child or mole needs to be evaluated for melanoma it should be done irrespective of the child’s age.

Melanoma can in rare cases cross the placenta, and placental evaluation and skin checks in newborns born to mothers with a history of invasive melanoma are advised. The youngest recorded death from melanoma was at 2 years of age.

Routinely, medical skin cancer examination should start around the age of 10 and continue on a second-yearly basis thereafter up to the age of 18, where annual checks are recommended. In families at high risk of melanoma this should be earlier.

Particular care should be taken at puberty and during adolescence when hormonal changes may activate moles and peer pressure can place demands on the child to get a tan or encourage outdoor activities that may result in sunburn.

Because melanoma families are on the lookout for the disease and seek professional consultation early, the survival rate for familial melanoma is higher than that for non-familial melanomas.

Types of Melanoma

There are several types of melanoma and they vary in their appearance, characteristics, site, and natural history. Invasive melanomas are more serious, as they penetrate deeper into the skin and are more likely to spread to other areas of the body.

Types of Melanoma include:

Superficial Spreading Melanoma (SSM)

Lentigo Maligna Melanoma (LMM)

Acral Lentiginous Melanoma (ALM)

Desmoplastic Melanoma (DM)

Uveal Melanoma (UM)

Mucosal Melanoma (MM)

Superficial Spreading Melanoma

Superficial Spreading Melanoma (SSM) also known as in-situ melanoma is by far the most common type, accounting for about 50 percent of all cases. This is the one most often seen in young people up to 40-50 years olds. As the name suggests, this melanoma can grow along the top layer of the skin for a long time in what is known as a radial growth phase. They may shift into a vertical growth phase and invade the skin and at this point are more likely to spread.

The first sign is the appearance of a flat or slightly raised discoloured patch that has irregular borders and is somewhat asymmetrical in form. The colour varies, and you may see areas of tan, brown, black, red, blue or white.

This type of melanoma can occur in a previously benign mole. This melanoma can be found almost anywhere on the body, but is most likely to occur on the trunk in men, the legs in women, and the upper back in both.

Amelanotic Melanoma

Amelanotic Melanoma is a type of skin cancer in which the cells do not make melanin. They can be pink, red, purple or of normal skin color, hence difficult to recognise. It has an asymmetrical shape, and an irregular faintly pigmented border.

Their atypical appearance leads to delay in diagnosis, the prognosis is poor and the rate of recurrence is high.

Amelanosis is often a sign of tumour aggression and genetic diversity within the melanoma - in that the cells are generally so abnormal they no longer perform even the basic function pigment cells perform - make pigment. Such lesions often have a worse outcome (prognosis) than most other forms of melanoma.

Lentigo Maligna Melanoma

Lentigo Maligna Melanoma (LMM) is similar to the superficial spreading type, accounts for 10 percent of all cases. It also has a prolonged radial growth phase on the surface, and usually appears as a flat or mildly elevated mottled tan, brown or dark brown discolouration in the mask area of the face (near eyes, cheeks, forehead, nose).

This type of in situ melanoma is found most often in the elderly, arising on chronically sun-exposed, damaged skin on the face, ears, arms and upper trunk. When this cancer becomes invasive, it is referred to as lentigo maligna melanoma.

Acral Lentiginous Melanoma

Acral Lentiginous Melanoma (ALM) is unique as it usually appears as a black or brown discolouration under the nails (Subungual melanoma) or on the soles of the feet or palms of the hands. It accounts for around 5 percent of melanoma cases.

This type of melanoma is sometimes found on dark-skinned people, and may advance more rapidly than superficial spreading melanoma and lentigo maligna. It is the most common melanoma in African-Americans and Asians, and the least common among Caucasians.

Nodular Melanoma

Nodular Melanoma (NM) is the most aggressive of the more common types of melanoma and is usually invasive at the time it is first diagnosed. It is one of the most dangerous forms of human cancer and accounts for 15-20 percent of all cases.

They are often distinguished by being Elevated, Firm, and Growing (EFG). They are usually black, but occasionally are blue, gray, white, brown, tan, red or even skin coloured.

The most frequent locations are the trunk, legs, and arms, mainly of elderly people, as well as the scalp in men.

20% of nodular melanomas have very little to no pigment, making a history of change the most reliable feature in diagnosing these lesions. The more rapidly these lesions grow the more important early removal is to survival rates.

Desmoplastic Melanoma

Desmoplastic Melanoma (DM) is a rare form of melanoma accounting for less than 1 percent of cases. It is a form of melanoma that is surrounded by fibrous tissue and may involve nerve fibres, when it does so it is called neurotropic melanoma.

Desmoplastic melanoma often lacks the classic ABCD features and is an aggressive form which needs to be considered whenever there is a lump (or nodule) that is growing on/in the skin, or when there is a change in a previously stable scar on the skin.

Uveal Melanoma

Uveal Melanoma (UM) may arise from the melanocytes that give the eye it’s colour on the iris, or from the melanocytes in the retina at the back of the eye (choroidal melanoma). These lesions are very rare and account for less than 1 percent of cases.

They can be very aggressive.

Mucosal Melanoma

Mucosal Melanoma (MM) does not arise in skin but instead arises from mucous membranes in areas such as the mouth, lips, sinuses, vagina, anorectal area, urethra, and so on. It is very rare accounting for less than 1 percent of cases, and there appears to be no link to UV exposure or to any of the other risk factors for melanoma, and these lesions are genetically distinct from other forms of melanoma.

They are often diagnosed at a late stage (for obvious reasons) and survival rates are generally quite low reflecting the delay in diagnosis.

Melanoma Screening

If you have a suspicious spot or mole, our Doctor will examine you with a dermoscope (mole magnifying instrument). Further diagnosis and management of your melanoma is best performed via a Full Body Scan. In the first incidence, this process includes

- Mapping a patient's entire body for any suspicious skin damage or lesion

- Followed by a detailed dermoscopic examination by a trained skin cancer specialist

- Recording and combining all images and skin metrics (size, shape, colour, and other attributes) into the patient record

Our expert Doctors at Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic will then clearly identify and diagnose any skin disease.

Self-exams can help you identify potential skin cancers earlier, when they can almost always be cured.

When you work together with the Doctors from the Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic by performing regular self-checking on the skin - studies show you are in the lowest risk group from skin cancer of any type.

Even if you have carefully practiced sun safety all summer, it's important to continue being vigilant about your skin in autumn, winter, and beyond. On the first day of every month you should examine your skin head to toe, looking for anything that’s changing in a unique way.

Stages of Melanoma

It may begin as a flat spot and become more elevated. In rare instances, it may be amelanotic, meaning it does not have any of the skin pigment (melanin) that typically turns a mole or melanoma brown, black or other dark colours. In these cases, it may be pink, red, normal skin colour or even other colours, making it harder to recognize as a melanoma.

Sometimes it can be hard to tell the difference between an atypical mole and an early melanoma. (Some melanomas begin within an atypical mole). The degree of atypical features in the mole can provide clues as to whether it is harmless, or at moderate or high risk of becoming a melanoma.

Moles are subject to change at certain times of life.

Once the type of melanoma has been established, the next step is to classify the disease as to its degree of severity.

The general stages of a melanoma are:

- T - stands for the main (primary) tumour (its size, location, and how far it has spread within the skin and to nearby tissues).

- N - stands for spread to nearby lymph nodes (bean-sized collections of immune system cells, to which cancers often spread first).

- M - is for metastasis (spread to other parts of the body).

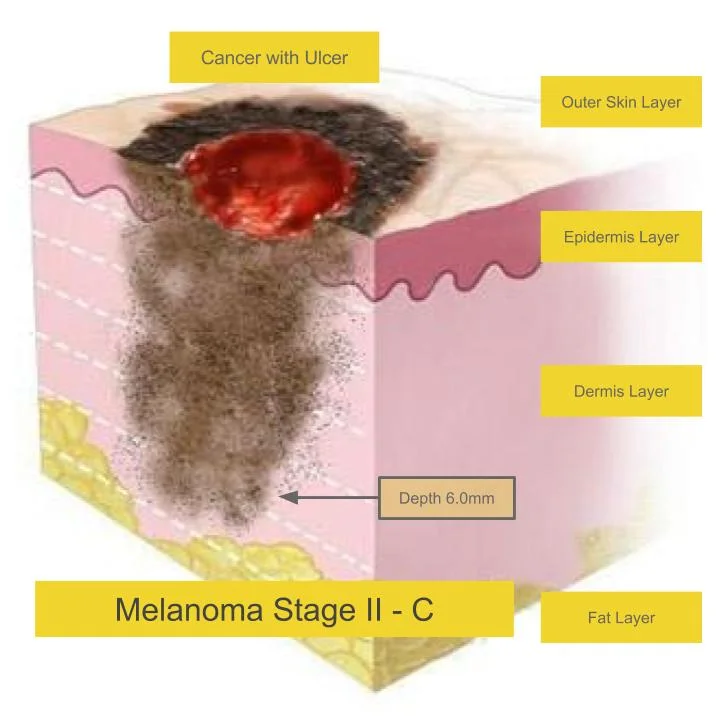

Clark Levels are useful when melanomas that have penetrated less than 1mm, and for more invasive lesions we use TNM Staging. There are five Clark Levels:

- Level 1 - melanoma confined to the epidermis (in situ melanoma)

- Level 2 - Invasion into the papillary dermis

- Level 3 - Invasion to the junction of the papillary and reticular dermis

- Level 4 - Invasion into the reticular dermis

- Level 5 - Invasion into the subcutaneous fat

TNM Staging refers not only to the depth of penetration but to the degree of spread. The staging of a melanoma is used to determine treatment, and may require additional tests to be done before the stage can be accurately determined. T means Tumour Depth, N means number of Nodes the melanoma has spread to, and M means the number of metastases (daughter melanomas that have broken off from the original).

If the excised lesion is thick, a biopsy of the first draining lymph node (sentinel node) is often performed. The most important feature in predicting outcome is tumour thickness (Stage 0 is less than 0.1mm, Stage I less than 2 mm, Stage II greater than 2 mm, Stage III spread to lymph nodes, and Stage IV distant spread).

If distant spread is suspected, CT scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis are performed. The blood test LDH can sometimes be useful to assess the presence of metastatic disease.

Thickness of the tumour, known as Breslow’s thickness (also called Breslow’s depth), is the most important in staging, but the appearance of microscopic ulceration (meaning that the epidermis on top of a major portion of the melanoma is not intact), and mitotic rate (how fast-growing the cancer cells are) are also important.

Clark Levels will enter into serious consideration for invasive melanoma only in the rare instances when mitotic rate cannot be determined.

To be precise, Breslow’s thickness measures the distance between the upper layer of the epidermis and the deepest point of tumour penetration in millimetres. The thinner the melanoma, the better the chance of cure. Therefore, Breslow’s thickness is considered one of the most significant factors in predicting the progression of the disease and the list below summarises the different depths reflected in the TNM Staging system:

- In situ (non-invasive) melanoma remains confined to the epidermis.

- Thinly invasive tumours with less than 1.0mm in Breslow depth.

- Intermediate invasive tumours are 1.0-4.0 mm in depth

- Thickly invasive melanomas are greater than 4.0 mm in depth

The presence of microscopic ulceration upgrades a tumour’s severity and can move it into a later stage. Therefore, the Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic Doctor may consider using a more aggressive treatment than would otherwise be used if ulceration is reported.

Mitotic rate (rate of melanoma cell division) has been introduced into the staging system based on recent evidence that it is also an independent factor predicting prognosis. The presence of at least one mitosis (cancer cell division) per millimetre squared (mm x mm) can upgrade a thin melanoma to a later stage at higher risk for metastasis.

Some melanomas are aggressive and can grow and spread (metastasise) quickly.

If melanoma is advanced the outcome (prognosis) can vary and affect your treatment choices.

More advanced melanomas (Stages III and IV) have spread (metastasized) to other parts of the body. There are also subdivisions within stages.

STAGE III Melanoma

By the time a melanoma advances to Stage III or beyond, an important change has occurred.

The Breslow’s thickness is by then irrelevant and is no longer included in staging, but the presence of microscopic ulceration continues to be used, as it has an important effect on the progression of the disease. At this point, the tumour has either spread to the lymph nodes or to the skin between the primary tumour and the nearby lymph nodes. (All tissues are bathed in lymph — a colourless, watery fluid consisting mainly of white blood cells — which drains into lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes throughout the body, potentially carrying cancer cells to distant organs).

A tumour is assigned to Stage III if it has metastasized or spread beyond the original tumour site. This can be determined by examining a biopsy of the node nearest the tumour, known as the sentinel node. Such a biopsy is now frequently done when a tumour is more than 1 mm in thickness, or when a thinner melanoma shows evidence of ulceration.

As the sentinel node biopsy is not necessary for every Stage III melanoma, you may wish to discuss the matter with your Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic Doctor.

In-transit or satellite metastases are also included in Stage III. In this case, the spread is to skin or underlying (subcutaneous) tissue for a distance of more than 2 centimeters from the primary tumour, but not to the regional lymph nodes.

In addition, the new staging system includes metastases so tiny they can be seen only through the microscope (micrometastases). Just how advanced the tumour is into Stage III (the “N” category, for “nodes”) depends on factors such as whether the metastases are in-transit or have reached the nodes, the number of metastatic nodes, the number of cancer cells found in them, and whether or not they are micrometastases or can be seen with the naked eye.

Stage IV Melanoma

The melanoma has metastasized to lymph nodes distant from the primary tumour or to internal organs, most often the lung, followed in descending order of frequency by the liver, brain, bone, and gastrointestinal tract.

The two main factors in determining how advanced the melanoma is into Stage IV (the “M” category, for “metastases”) are the site of the distant metastases (nonvisceral, lung, or any other visceral metastatic sites) and elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level.

Lymph Node Involvement

Once a melanoma has progressed beyond Stage II, it has spread beyond the original site. It is most likely to have reached the lymph nodes that are closest to the tumour.

Palpable nodes

To find out whether melanoma cells have escaped the primary tumour, the Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic Doctor starts by feeling the nearby lymph nodes.

When there is an enlargement or lump in a lymph node, it is described as “palpable,” meaning that the Doctor can feel it on physical examination. If a node is clinically positive this will be evaluated in more detail by your Doctor at the Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic through the use of high resolution ultrasound, and a fine needle aspirate from a suspicious node may be sent for confirmatory testing.

An enlarged lymph node may instead be surgically removed and sent to the pathology laboratory to be tested microscopically for the presence of malignant cells. If any are found, the rest of the nodes in that basin will also be removed, and treatments that stimulate the immune system and/or therapies directly targeting the melanoma may be recommended.

Non-palpable nodes

The lymph nodes are not always palpable even when melanoma cells have spread beyond the original tumour. In the past, there was much debate about when to excise and examine the local lymph nodes. Some believed in a wait and see policy; others believed in removing all the nodes (radical node dissection) in the region of the tumour on the chance there were hidden cancer cells; this was called elective lymph node dissection, or ELND.

Lymphoscintigraphy (Mapping) & Sentinel Node Biopsy

Today, there are specific guidelines for when to investigate the regional lymph nodes: Two techniques refined over the past decade, called lymphoscintigraphy and sentinel node biopsy, have solved the problem of whether or not to perform radical lymph node dissection in the absence of clinically palpable nodes.

Generally, when patients have melanomas under 1 mm in thickness, without ulceration and a mitotic rate of less than 1/mm2, nodal dissection is deemed unnecessary. For melanomas that have reached 1 mm in thickness, and/or have ulceration or a mitotic rate of 1/mm2 or greater, lymphoscintigraphy and sentinel node biopsy (SLNB) are undertaken to determine whether all the nodes in the regional lymph node basin should be removed.

Lymphoscintigraphy is a technique for mapping the lymphatic pathway to track whether melanoma cells have metastasized from the primary melanoma tumour to the local lymph nodes. A small amount of a harmless radioactive substance is injected at the site of the melanoma to trace the flow of lymph fluid draining from it to the nodes. Then, with the help of a scanner, the drainage pattern of the lymph fluid is determined.

Most often, a second lymphatic mapping technique is then also used to increase certainty: Blue dye is injected into the skin around the tumour, and the dye passes into the lymph fluid, tracing its path. The blue colour is picked up first by the node closest to the tumour, which is referred to as the sentinel node. Sometimes there are one or more other sentinel nodes as well, which should also show up in the dye and radioactive tracer tests. Armed with the findings from this lymphatic mapping, the surgeon can at first remove only the sentinel nodes.

Once a specific area (basin) of lymph drainage has been pinpointed by the dye or tracer, the sentinel node(s) can be removed surgically and tested in the pathology laboratory, the premise being that if any melanoma cells reach the local nodal basin, they will show up in the sentinel node(s). If no cancer cells are found in the sentinel nodes, no further surgery is performed. If cancer cells are present in the sentinel nodes, the rest of the nodes in this lymphatic basin will also usually be removed and examined. Once melanoma cells are confirmed in the lymph nodes, the patient is reclassified as Stage III.

Microscopic Nodal Involvement

Research is now also exploring special biochemical techniques that can identify those melanoma cells that do not show up in the course of routine microscopic examination and sentinel node biopsy. Research is currently being done on blood tests that may be able to detect metastatic or in transit disease and initial results are encouraging.

Local vs Distant Spread

Once the disease has advanced to Stage IV, melanoma cells have travelled through the body via the bloodstream or lymph vessels, going far from the original tumour site. They may have reached distant lymph nodes or invaded the internal organs. This can be in addition to or instead of in-transit metastases or local spread to the regional lymph nodes. In local forms of the disease, the metastases can reach skin or subcutaneous tissue more than 2 cm from the primary tumour, but not beyond the regional lymph nodes.

When distant metastases are suspected, they can be traced by scans of the chest, head, abdomen, and pelvis with a CT (computed tomography) scan in which special X-ray equipment and a computer program show a cross-section of body tissues or organs; an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan that uses a magnet instead of X rays to create a map of the patient’s body and brain; and by PET (positron emission tomography), an evolving radiographic technique. For PET scanning, radioactive sugar, the basic carbohydrate utilized by the body for energy, is injected intravenously into the patient. This sugar is preferentially taken up by any melanoma cells than surrounding normal tissues.

Melanoma Diagnosis

An excision biopsy is generally required to confirm the diagnosis and to guide effective treatment. This diagnostic process involves a Doctor taking a tissue sample for biopsy by removing the lesion surgically under local anaesthetic to a margin of 2mm and sending it for histopathological evaluation.

Excision biopsy is sufficient to establish the diagnosis of a melanoma. In the rare case of suspected metastatic melanoma, lymph nodes may be examined by the Doctor to see if the cancer has spread or by the use of imaging technologies like ultrasound, CT, or PET scanning.

Untreated Melanomas

Melanomas can spread to vital organs, but s respond well to early treatment. If untreated the consequences could include:

- Disfigurement

- Nerve, or muscle injury, or other injury to nearby unique structures like eyelids from the melanoma itself or it’s required treatment

- They are most likely to be lethal in almost all cases if untreated.

The larger the tumour has grown, the more extensive any surgical or adjuvant treatment would be. In 2016 it is estimated that there will be 1,774 deaths from melanoma in Australia.

Melanoma Treatment Options

Surgical Removal for Melanoma

Surgical removal of the melanoma is the most common treatment. Melanomas are almost always surgically removed under local anaesthetic. This approach offers:

- High cure rates

- Is immediate

- Margins are checked to confirm complete removal

- The presence of any invasive component can be accurately assessed guiding further treatment

In more advanced skin cancers, some of the surrounding tissue may also be removed to make sure that all of the cancerous cells are cleared.

Excision Treatment Process - After careful administration of local anaesthetic, the Doctor uses a scalpel to remove the entire growth, along with surrounding apparently normal skin as a safety margin.

The wound around the surgical site is then closed with sutures (stitches).

Excision Treatment Recovery - For a few days post excision there may be minor bruising and swelling. Scarring is usually quite acceptable. Pain or discomfort is usually minor.

Typically, where sutures are used, they are removed soon afterwards.

Wide-Area Local Excision - A second excision is usually performed on the site after the melanoma has been diagnosed on excisional biopsy. The desired safety margins are determined by the type of melanoma to be between 5mm and 20mm based on the level of invasion and a second excision known as a wide-area local excision is performed to achieve this amount of safety margin around the melanoma excision site. In cases of superficial spreading melanoma the desired margin is 5 mm to the side and deep, and highly invasive melanomas may require up to 20mm margins to the side and deep to reach the lowest risk of spread or local recurrence.

Topical Chemotherapy - Imiquimod for Melanoma

This is currently being researched - and is a prescription only cream that is being evaluated for the treatment of biopsy-proven superficial melanomas that are not otherwise suitable for surgical removal, but is not appropriate for use on invasive melanomas.

General Prognosis After Treatment

The most important factor in melanoma survival is early diagnosis and treatment.

An individual’s prognosis depends on the type and stage of cancer, as well as their age and general health at the time of diagnosis. Five year survival for people diagnosed with melanoma is 91%, rising to 99% if the melanoma is detected before it has spread.

If spread is within the region of the primary melanoma (ie to local lymph nodes or to skin in the local area), the five year survival is 65%, dropping to 15% if the disease is widespread and goes untreated.

In Australia in 2016, it is estimated there will be 1,744 deaths due to melanoma.

Melanoma is the sixth most common cause of cancer death in Australian men and tenth most common in Australian women.

Melanoma Recurrence

Doctors at the Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic have seen a significant increase in the number of patients in their twenties and thirties are being treated for melanoma over the last 17 years.

Men with melanoma have outnumbered women with the disease, but more women are getting melanomas than in the past.

Regular checks at the Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic should be performed so that not only the site(s) previously treated, but the entire skin surface can be examined, and mapped digitally and compared to the images taken at subsequent skin checks.

Melanomas on the scalp and nose are especially troublesome, with higher rates of recurrence and with these recurrences typically taking place within the first two to three years following surgery.

Should a cancer recur, your Doctor might recommend a different type of treatment.In some cases referral to a specialised Unit like the Sydney Melanoma Unit may be necessary.

Melanoma Prevention

Anyone who has had one melanoma has an increased chance of developing another, especially in the same skin area or nearby. That is usually because the patient’s skin has already suffered irreversible sun damage.

Thus, it is crucial to pay particular attention to any previously treated site, or any areas of change should be shown to your Doctor at the Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic immediately.

Melanomas on the nose, ears, and lips are especially prone to recurrence.

Even if no suspicious signs are noticed, regularly scheduled follow-up visits including total-body skin exams are an essential part of post-treatment care every 6 months.

To prevent melanoma make sure you follow the recommendations below:

- Seek the shade, especially between 10am and 3pm when UV levels are most intense

- Avoid sunburn by minimising sun exposure when the SunSmart UV Alert exceeds 3 and especially in the middle of the day in the warmer half of the year

- Avoid tanning and never use UV tanning beds

- Cover up with clothing, including a broad-brimmed hat and UV-blocking sunglasses

- Use a broad spectrum (UVA/UVB) sunscreen with an SPF of 30+ or higher every day. For extended outdoor activity, use a water-resistant, broad spectrum (UVA/UVB) sunscreen with an SPF of 30+ or higher

- Apply sunscreen to your entire body 10 minutes before going outside. Reapply every two hours or immediately after swimming or excessive sweating, or towelling down

- Keep newborns out of the sun. Sunscreens should be used on babies over the age of six months

- Examine your skin head-to-toe every month looking for unique changes.

If you see unique changes anywhere and of any kind, keep an eye on it and if it continues to change for more than 2-3 weeks the notify the Bondi Junction Skin Cancer Clinic without delay.